How Luca Page built Radically Fit, an inclusive, community-based gym

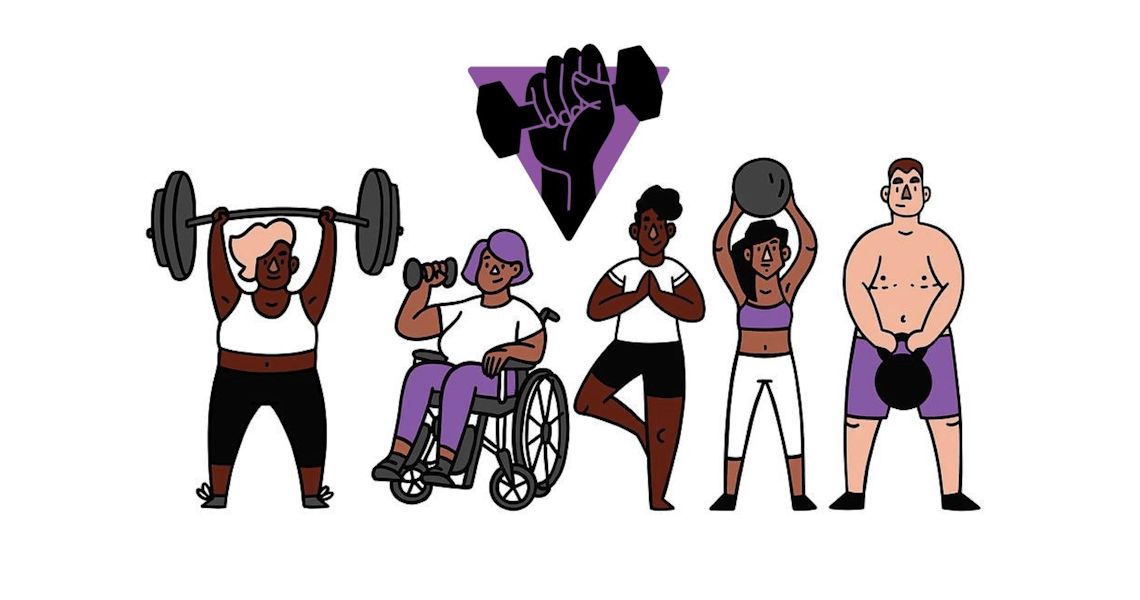

Many of us see exercise as a to-do list item: While we might not love it, we feel obligated to check it off. But for Luca Page – founder of Radically Fit, a gym in Oakland, CA that centers LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and bigger-bodied people – it carries deeper meaning. Movement helped them heal.

Page played soccer, basketball, and other sports until high school, when they switched gears to focus on vocal performance. “I kind of lost my mind-body connection,” they recall. But that all changed at age 18, after the death of a close friend. Their grief left them struggling with simple, everyday tasks, like climbing out of bed and even drinking water. They often dissociated from their surroundings. Eventually, they dropped out of college.

Besides therapy and the support of their friends, Page, now 34, credits exercise with drawing them out of that dark headspace. “For the time that I was at the gym and I was moving my body, I was really able to focus on myself and even be aware of how my body was moving,” they say. “That was when, as an adult, I became really aware of the connection that exercise and mental health have.”

We all deserve the mental health benefits of exercise – but trans and other gender expansive people have less access to them than their straight, cis counterparts, Page points out. That’s partly because gyms, whether intentionally or not, generally aren’t welcoming of LGBTQ+ people. The staff members tend to be straight and cis, for instance, and neglect to recognize pronouns. Likewise, many gyms alienate BIPOC and bigger-bodied people by, say, employing mostly white trainers and idealizing thinness.

“As a queer person, as a trans person, as a bigger-bodied person, as a brown person, one of the first things that occurs when I show up in a lot of fitness places is the feeling of being othered,” Page says. In 2018, they opened Radically Fit, a community-based gym that does the opposite – serving LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and bigger-bodied folks first and foremost.

Radically Fit is part of a recent rise in LGBTQ-inclusive gyms that also includes Solace in New York City, Reaction Fitness Collective in Greenville, South Carolina, and Non Gendered Fitness in Melbourne, to name a few. Many of these gyms center on BIPOC and bigger-bodied people, too.

Centering LGBTQ and other marginalized communities in gyms is more than a matter of kindness – it’s a matter of justice. Due to the stress of discrimination, among other factors, people with LGBTQ+ and other marginalized identities have a higher risk of mental health issues and therefore arguably stand to benefit more from the psychological healing fitness can offer than those who conform to what society deems “the norm.”

Yet society denies them even this. LGBTQ+ people are othered not only by gym culture, but also laws designed to further exclude them from sports and fitness. Arizona, Oklahoma, Iowa, and several other states, for example, recently banned trans youth from playing on school sports teams that align with their gender identity.

“The things that we stand for and the things that we strive to provide for folks [at Radically Fit] are in so many ways the opposite of what marginalized people are given in this world,” Page says. “There needs to be spaces like this where folks can move their bodies and feel safer doing it.”

Getting Radically Fit off the ground

Around seven years after integrating exercise into their daily life, Page left their admin job at an adoption agency – the same one they were adopted through – and pursued a personal training career, inspired by the positive impact personal trainers had on their own fitness journey. They worked at a few gyms before landing a fitness director position at a friend’s body work studio. In 2018, they bought out its fitness program, which became Radically Fit.

Page spoke with Invoice2go, a Bill.com company, over Zoom from their sunlit kitchen, periodically adjusting their dark-rimmed glasses and sipping a mug of coffee. “I started Radically Fit because there was such a lack of space in Oakland, and just everywhere, that really prioritized and centered big bodies and fat bodies and queer and trans folks and Black folks and people of color,” they say. Plus, their conversations with community members revealed they wanted and needed a space like this.

Page set up shop at another friend’s gym for a few months before securing Radically Fit’s current location. Because they’d bought out their friend’s fitness program, they already had a strong baseline of customers. But to bring even more people through the door, they sent a flurry of email newsletters and started an Instagram account. They also hosted community workouts, inviting anyone to test-run the space and meet the staff, and threw a grand opening party.

A major hurdle that LGBTQ+ and other marginalized people face in starting businesses is access to capital, Page says. BIPOC receive less business financing than their white counterparts, and are less likely to have friends and family who can chip in. Backstage Capital estimates that less than 1% of VC deals are awarded to LGBTQ+ founders.

Page considers themself lucky – they were able to borrow money from a community member. “As a brown person who didn’t have credit, is just now building their credit, I wouldn’t have been able to get a loan from a bank,” they say.

While there are business centers where marginalized people without formal business training can learn business management skills, Page says, many aren’t staffed by people who share their identities. Fortunately, a community member helped Page with bookkeeping, budgeting, and other business management skills, at least initially, while others offered emotional support.

Practicing self-care and seeking help from loved ones is essential in those first few years of launching a business, especially for entrepreneurs with marginalized identities, Page says. “There are going to be moments when you feel like you’re floundering, and you’ve made a mistake in doing what you’re doing. But if you have folks who can hold you, remind you why you set out to do this, and encourage you to stay on the path, it makes a huge difference.”

Fighting toxic fitness culture

Many of the practices we accept as part and parcel of gym culture actually harm marginalized people, Page says. And because of a general lack of diversity in hiring, marginalized people often don’t see anyone who looks like them when they step foot in a gym, they add, which can also create discomfort. Even the physical space itself – like gendered restrooms and locker rooms that lack spaces for gender-expansive people – can feel unwelcoming, or worse, unsafe.

The language used at conventional gyms can also be damaging, according to Page. Staff members typically don’t consider whether they’re using members’ correct pronouns, running the risk of disrespecting their gender identities and triggering dysphoria. Fatphobic comments also abound, like “I need to burn off the pizza I ate last night” or “I’m working out because I feel fat.”

Page knows firsthand what it’s like to navigate spaces that exclude them, having been adopted by white parents and raised in a predominantly straight, white, wealthy community in Silicon Valley. Moving to Oakland – which ranks among the most diverse cities in the US – at age 25 opened their eyes to the racism that had permeated their youth, and fueled their desire to create spaces with others working to disrupt it.

Around the same time, they consistently felt othered while working as a women’s boot camp instructor at a conventional gym. “I often felt like, because I didn’t fit what most of these women assumed a fitness instructor looked like, they didn’t respect me, and they questioned me a lot more than I think I needed questioning,” Page recalls.

Making space for every body

Radically Fit’s efforts to remove the barriers Page and other marginalized people face at conventional gyms begin with intentionality. Every decision about the business is guided by its mission: “to serve the LGBTQ/POC community by offering an inclusive, body positive, safe space for anyone to workout and build strong relationships.”

For Page, that means creating a space that not only supports LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and bigger-bodied people, but hires them into leadership positions. As it stands, Radically Fit is entirely staffed by BIPOC. “It’s really important for folks, especially fat people, especially non-white people, to see thesmelves in other people doing things they might have been told their whole life they couldn’t do,” Page explains. They add that seeing instructors who look like them might also inspire members to enter the fitness industry, with Radically Fit offering a jumping-off point.

Radically Fit staff members are also extremely mindful of their language. They don’t talk about food, use shame-based motivation, or encourage clients to push past their limits. Instead, they meet members where they are. This includes resisting ableism through an awareness that each client has different physical capabilities – which can vary from day to day – and a willingness to adjust workouts accordingly so they can move in a way that feels best for them.

Meanwhile, Radically Fit offers classes that prioritize the most oppressed within the LGBTQ+ community, including those who live at the intersections of other marginalized identities. Trans and GNC (Gender Nonconforming) Mind-Body Alignment – which might include, say, people preparing for top surgery who want to build their chests and shoulders – allows students to engage in movement that affirms their gender identities. In similar vein, Black and Brown Queers carves out space for people with these identities to work out in community with each other, without fear of the casual racism they might encounter elsewhere. And Big Buff Babes, which Page teaches, enables fat and bigger-bodied people to move free of judgment or shame.

Page and their team have also built a physical space that supports all bodies. They have non-gendered bathrooms and no mirrors. “From my experience and those of other folks who are fat and bigger-bodied, mirrors can be really, really triggering,” Page explains, who finds instructor feedback to be more helpful than their reflection in ensuring proper form. They add that mirrors can also trigger body dysphoria in trans and gender nonconforming folks.

Radically Fit’s mission also shapes its marketing, which spotlights the marginalized community members it strives most to serve. Instagram remains its primary means of attracting new members. Although Page has managed the account since the gym’s founding, they admit they’re not “great at it.” “I think that the reason it has worked without a strategy, technically, is because it’s just been authentic,” they say. “It’s just been, ‘This is who we are. This is what we’re doing.’”

Listening is key: The Radically Fit team tailors its services to members’ needs, based on informal conversations and responses to email requests for feedback. Page advises anyone seeking to open an inclusive, community-based space to talk to people who are already doing racial and social justice work. Ask community members what they want and need, and make sure your actions align with your mission statement. “If you’re a white queer or trans person, think really deeply about how you can use your privilege and your power and all that comes with being white to uplift Black and brown people that are already doing this work,” Page says.

Turning to community during COVID

A sliding scale membership program, which allows members to pay what they can, allows Radically Fit to stay accessible not only to people of all identities, but of all income levels, too.

At the same time, the marginalized communities Radically Fit serves generally don’t have much wealth, Page explains, making it a challenge to move beyond surviving month to month. Page is mindful of the delicate balance between sustaining their business and serving their community in the ways they want to. Despite starting out with a specific vision for Radically Fit, they’ve tried to stay open to pivoting as they and their team figure out a more sustainable business model.

The pandemic didn’t help matters, forcing Radically Fit to move online for a year before relaunching in-person workouts briefly last June and again this March. But thanks to the loyalty of its members, the gym managed to stay afloat and Page was able to retain their staff.

From March to May, Radically Fit is turning to their community for support again, this time with a Spring Fundraiser to help keep its doors open through another year of the pandemic. The funds will cover the cost of rent, staff, additional classes, and efforts to lay the groundwork for future growth, Page says. Importantly, they’ll allow membership to remain financially accessible to everyone. Donors are eligible for entry in a raffle, whose prizes range from artwork to a trap yoga flow.

“I want to be in a position where I don’t need help from other people to keep this business open,” Page says. “But the reality is, this is a community-based business, and for things to be symbiotic, it needs to also be fed by the community.” Indeed, among the biggest lessons they’ve learned is that they can’t run a community-based business without the support of their community, especially during a pandemic – as uncomfortable as it makes them feel to ask for it.

Looking toward the horizon, Page hopes to open Radically Fit in more cities in the US. “I would love for it to be a space where folks are really finding their way home from being in a system that constantly tells them that they are not worthy of love as they are today,” they say.

They’d also love for Radically Fit to work with LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and bigger-bodied community members beyond its walls to shake up the fitness industry. “Who knows? It would be an amazing thing to see, 10, 15 years down the line, a really big shift in how fitness culture is run, who is in it, and who is centered,” Page says. “We would love to be a part of that.”

Related Articles

How to accept credit card payments on Invoice2go in 3 simple steps

Accept payments online via Apple Pay and Google Pay

Must-not-miss write-offs as you wrap up 2022 year-end finances

5 ways accepting credit and debit card payments helps your business stay resilient

4 easy ways to increase cash flow today

What is Small Business Saturday and why is it important?

The features and surprising benefits of a well-designed packing slip